August 10, 2020

A Long History of Conserving the Lion

- as seen by -

Luke Hunter

Luke Hunter

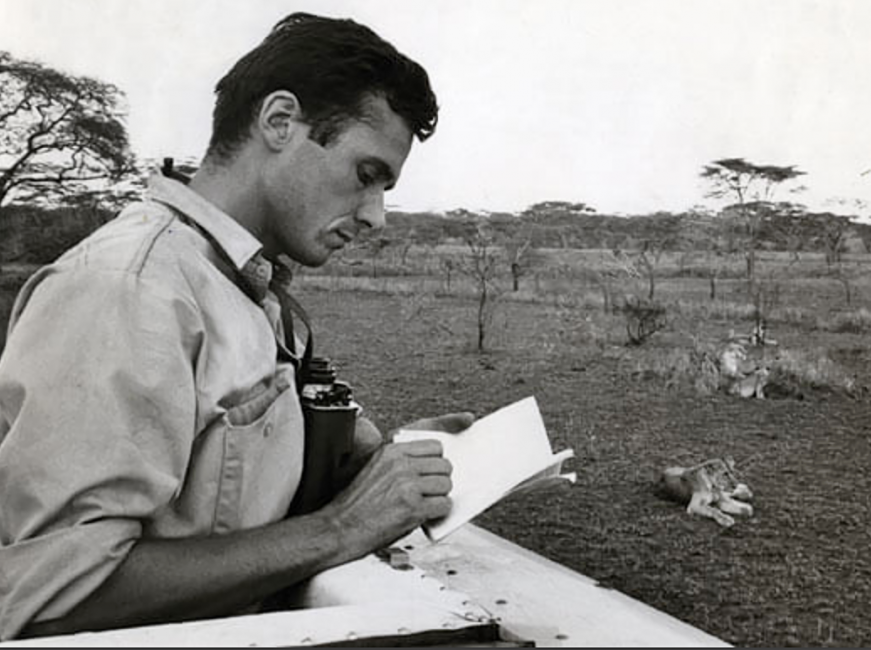

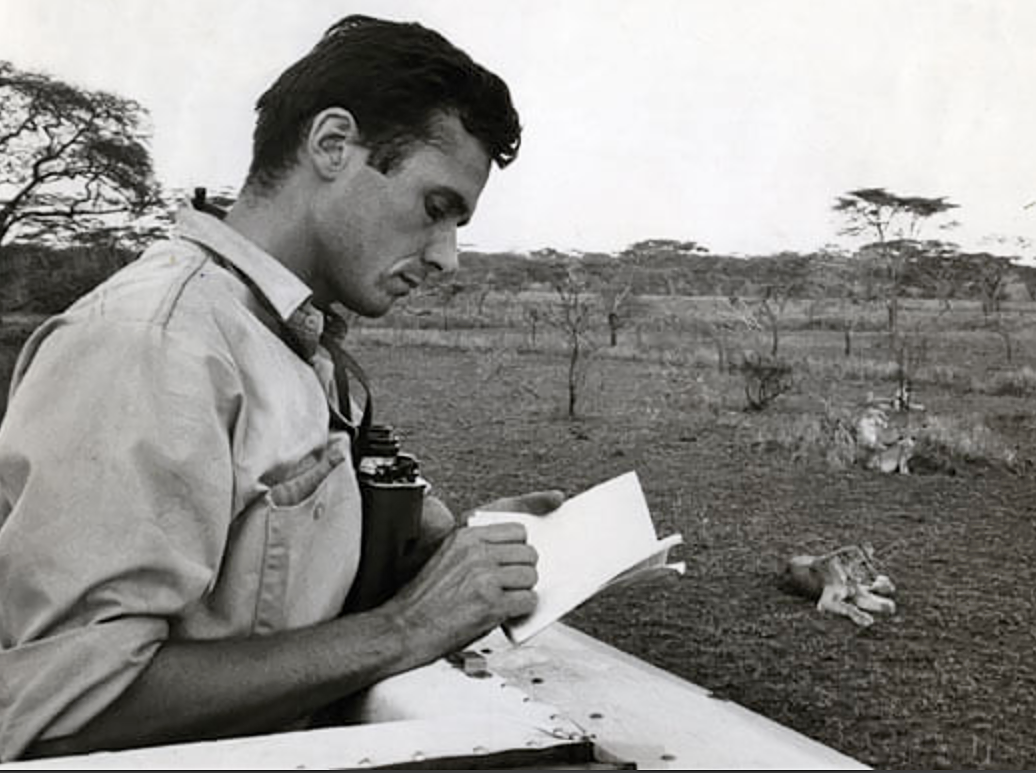

Two years before I was born, a man called George Schaller (above, with African lions) was hired by the New York Zoological Society (Wildlife Conservation Society’s name until 1993) to study the African lion in Tanzania’s famous Serengeti National Park. As the NYZS’s Annual Report of 1966 notes:

“Despite wide interest in lions, basic ecological and behavioral studies such as these have very seldom been undertaken previously because they place such heavy demands on the patience and stamina of the observing zoologist.”

Heavy demands were evidently no hardship for George. By 1973 – I was five then – he had published three books on his research. One of them, The Serengeti Lion (1972) is still in print and still the most comprehensive, scholarly title ever published on the species. George’s work set the standard for all lion researchers who followed, myself among them, who still attempt to emulate his patience and stamina. And it began a long history for WCS of lion conservation.

From that pioneering study 55 years ago, WCS’s lion footprint has blossomed across nine African countries with an estimated 4500 adult lions living in WCS landscapes. In the intervening decades, Africa’s great cat has not fared well. The number of lions inside the Serengeti National Park has not changed much from when George studied them, but it is an outlier. Elsewhere the species has mostly declined, in some cases precipitously. Outside of four southern African countries where lions are stable or increasing, populations are down by sixty percent since the early 1990s when I first started working on the species.

WCS’s landscapes give sanctuary to many of the most imperiled lion populations where extreme poverty, insecurity, and increasingly severe climatic perturbations create formidable challenges to conservation. Yet our commitment to remaining on the ground, for as long as it takes, prevails. It is the reason that many of these populations have not already vanished. It also underlies a long-term pledge to restoring them to their former numbers. Over the next 25 years, WCS will work to increase lion numbers in the sites where we work by at least fifty percent – 2000 to 2250 more wild lions. In some landscapes, the potential for recovery is even greater.

I am reminded of WCS’s long history every time I sit down to work in my home office. Next to my laptop sits the skull of one of George’s study lions, a male who was killed in a territorial clash with rival males more than half a century ago. His was a fairly typical, natural fate of aging male lions in times past. Today, humans rather than natural causes are the main reason that adult lions die in many populations. Our vision for lions reverses that pattern, by stopping poaching, resolving human-lion conflict, and bringing benefits to the people who live alongside them. It is led by the next generation of African conservationists and biologists following in George’s footsteps, people like Roger Fotso, Noah Mpunga, and Simon Nampindo who head three of our most important country programs for lions. If we succeed, local people will have fewer incentives to kill lions. And the lions will be able to live and die like George’s lions, much as they have for millennia.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Wildlife Conservation Society is celebrating 125 years of saving wildlife and wild places in 2020. WCS was founded as the New York Zoological Society in 1895. Wild View will feature regular posts on the history of the Society’s photography and other events throughout the year.

Today is World Lion Day, a time to check out global efforts to protect lions and end the decline of wild lion populations.

Leave a Comment